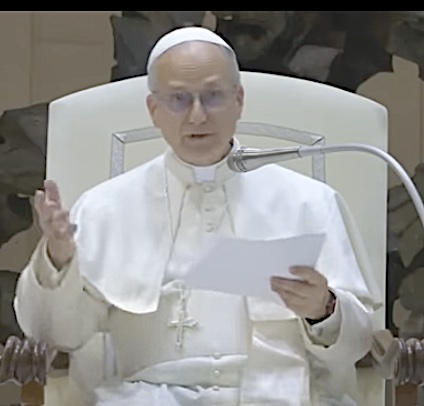

Pope Leo xiv Address to the Diplomatic Corps accredited to the Holy See

Clementine Hall = Friday, May 16, 2025

Your Eminence,

Your Excellencies,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Peace be with you!

I thank His Excellency Mr. George Poulides, Ambassador of the Republic of Cyprus and Dean of the Diplomatic Corps, for the cordial words he addressed to me on behalf of all of you and for his tireless work, which he carries out with vigor, passion, and kindness that distinguish him, qualities that have earned him the esteem of all my predecessors whom I have met during these years of mission at the Holy See and, in particular, of the late Pope Francis.

I would also like to express my gratitude for the many messages of good wishes that followed my election, as well as for the messages of condolence on the death of Pope Francis, that preceded them, even from countries with which the Holy See does not have diplomatic relations.

This is an important sign of esteem, that encourages the deepening of mutual relations.

I hope that in our dialogue there will always be a sense of family – the diplomatic community represents the whole family of peoples – sharing the joys and sorrows of life and the human and spiritual values that animate it.

Indeed, papal diplomacy is an expression of the Church’s very catholicity, and in its diplomatic action the Holy See is animated by a pastoral urgency that leads it not to seek privileges but to intensify its evangelical mission at the service of humanity.

It fights against all indifference and constantly calls consciences to account, as my venerable Predecessor did tirelessly, always attentive to the cry of the poor, the needy and the marginalized, as well as to the challenges that mark our times, from the protection of creation to artificial intelligence.

In addition to being a concrete sign of your countries’ attention to the Apostolic See, your presence here today is a gift for me, which allows me to renew the Church’s and my own desire to reach out to embrace every people and every individual on this earth who yearns and needs truth, justice, and peace!

In a certain sense, my own life experience, which has unfolded in North America, South America, and Europe, is representative of this desire to cross borders in order to meet different peoples and cultures.

Through the constant and patient work of the Secretariat of State, I intend to consolidate my knowledge and dialogue with you and with your countries, many of which I have already had the grace to visit during my lifetime, especially when I was Prior General of the Augustinians.

I trust that Divine Providence will grant me further opportunities to meet the realities from which you come, so that I may welcome the opportunities that will arise to confirm in the faith so many brothers and sisters scattered throughout the world and to build new bridges with all people of good will.

In our dialogue, I would like us to keep in mind three key words, which are the pillars of the Church’s missionary activity and the work of the Holy See’s diplomacy.

The first word is peace.

Too often we think of it a “negative” word, that is, as the mere absence of war and conflict, since opposition is part of human nature and always accompanies us, too often forcing us to live in a constant “state of conflict”: at home, at work, in society.

Peace then seems like a simple truce, a moment of rest between one dispute and another, but, no matter how hard we try, tensions are always present, a bit like embers smoldering under the ashes, ready to reignite at any moment.

From a Christian perspective – as in other religious experiences – peace is first and foremost a gift: Christ’s first gift: “I give you my peace” (Jn 14:27).

However, it is an active, committed gift that involves and commits each one of us, whatever our cultural background or religious affiliation, and which requires, first and foremost, work on ourselves.

Peace is built in the heart and from the heart, by eliminating pride and pretensions, and by measuring our words, because words can also hurt and kill, not only weapons.

In this perspective, I believe that religions and interreligious dialogue can make a fundamental contribution to fostering contexts of peace.

This requires, of course, full respect for religious freedom in every country, since religious experience is a fundamental dimension of the human person, without which it is difficult, if not impossible, to achieve the purification of the heart necessary for building peaceful relationships.

Trom this work, which we are all called, the premises of every conflict and every destructive desire for conquest can be eradicated.

This also requires a sincere willingness to engage in dialogue, animated by the desire to meet rather than to clash.

In this perspective, it is necessary to give new impetus to multilateral diplomacy and to those international institutions that were conceived and created primarily to resolve disputes that might arise within the international community.

Of course, there must also be a willingness to stop producing instruments of destruction and death, since, as Pope Francis recalled in his recent Urbi et Orbi message, “there can be no peace without genuine disarmament [and] the need for each people to provide for its own defense must not turn into a general arms race.”

The second word is justice.

The pursuing of peace requires the practice of justice.

As I said, I chose my name thinking first of Leo XIII, the Pope who wrote the first great social encyclical, ‘Rerum Novarum’ (translates as ‘ New Things’)

In the epochal change we are experiencing, the Holy See cannot fail to raise its voice against the many inequalities and injustices that lead, among other things, to degrading working conditions and to increasingly fragmented and conflict-ridden societies.

Efforts must also be made to redress global inequalities, where see opulence and poverty create deep divisions between continents, countries, and even within individual societies.

It is the responsibility of leaders to work to build harmonious and peaceful civil societies.

This can be done first and foremost by investing in the family, founded on the stable union between a man and a woman, “the smallest but true society, and the first civil society” [Leone XIII, Lett. enc. Rerum novarum (15 May 1891), 8 & 9. – see footnote below].

Moreover, no one can fail to promote an environment in which the dignity of every person is protected, especially the weakest and most defenseless, from the unborn to the elderly, from the sick to the unemployed, whether they are citizens or immigrants.

My own story is that of a citizen, a descendant of immigrants, who himself emigrated.

In the course of our lives, each of us may find ourselves healthy or sick, employed or unemployed, at home or abroad: but our dignity always remains the same, that of a creature loved and wanted by God.

The third word is truth.

Truly peaceful relationships cannot be built without truth, even within the international community. Where words take on ambiguous and ambivalent connotations and the virtual world, with its altered perception of reality, takes over unchecked, it is difficult to build authentic relationships, because the objective and real premises of communication are lacking.

The Church for her part, can never exempt itself from speaking the truth about man and the world, resorting when necessary to blunt language, that may initially cause some misunderstanding.

But truth is never separated from charity, which always has at its root a concern for the life and well-being of every man and woman.

Moreover, from a Christian perspective, truth is not the affirmation of abstract and disembodied principles, but the encounter with the person of Christ himself, who lives in the community of believers. Thus, far from distancing us, truth enables us to face with greater vigor the challenges of our time, such as migration, the ethical use of artificial intelligence, and the protection of our beloved earth.

These are challenges that require the commitment and collaboration of all, because no one can think of facing them alone.

Dear Ambassadors,

My ministry begins in the heart of a Jubilee Year, especially dedicated to hope.

It is a time of conversion and renewal, and above all an opportunity to leave disputes behind us and begin a new journey, animated by the hope of being able to build, working together, each according to his or her own sensitivity and responsibility, a world in which everyone can realize his or her humanity in truth, justice, and peace.

I hope that this will happen in all contexts, beginning with the most difficult, such as Ukraine and the Holy Land.

I thank you for all the work you do to build bridges between your countries and the Holy See, and I cordially bless you, your families, and your peoples. Thank you!

[Blessing]

And thank you for all the work you do!

__________________________________________________

Footnote: Leone XIII, Lett. enc. Rerum novarum (15 maggio 1891), 8 & 9.

8. The fact that God has given the earth for the use and enjoyment of the whole human race can in no way be a bar to the owning of private property.

For God has granted the earth to mankind in general, not in the sense that all without distinction can deal with it as they like, but rather that no part of it was assigned to any one in particular, and that the limits of private possession have been left to be fixed by man’s own industry, and by the laws of individual races.

Moreover, the earth, even though apportioned among private owners, ceases not thereby to minister to the needs of all, inasmuch as there is not one who does not sustain life from what the land produces. Those who do not possess the soil contribute their labor; hence, it may truly be said that all human subsistence is derived either from labor on one’s own land, or from some toil, some calling, which is paid for either in the produce of the land itself, or in that which is exchanged for what the land brings forth.

9. Here, again, we have further proof that private ownership is in accordance with the law of nature. Truly, that which is required for the preservation of life, and for life’s well-being, is produced in great abundance from the soil, but not until man has brought it into cultivation and expended upon it his solicitude and skill.

Now, when man thus turns the activity of his mind and the strength of his body toward procuring the fruits of nature, by such act he makes his own that portion of nature’s field which he cultivates – that portion on which he leaves, as it were, the impress of his personality; and it cannot but be just that he should possess that portion as his very own, and have a right to hold it without any one being justified in violating that right.